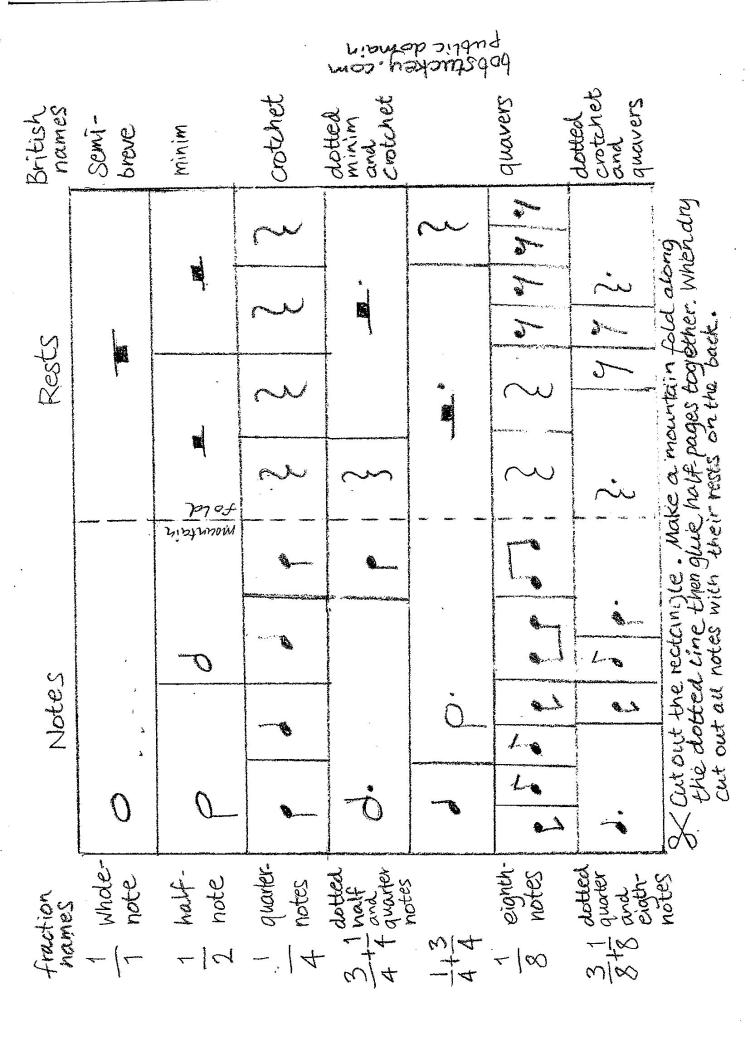

The way musicians write down rhythms has taken shape over hundreds of years. It has strange rules. Notes can be flipped upside down without changing their length but rests cannot. The dot to the right of either a note or rest increases its length by a half. Get out your scissors and glue and print our this chart to get a grasp of the sizes of notes and rests. You can arrange them in any order, in one long line, or choose a bar length, e.g 4/4, 3/4 or 2/4, and set them below each other. You can also line them up on the white keys of the piano, each key fitting a quarter-note (aka crotchet).

You can also experiment with different sized bars, 4/4, 3/4, 2/4, 3/8 and 2/8 by printing out this sheet.

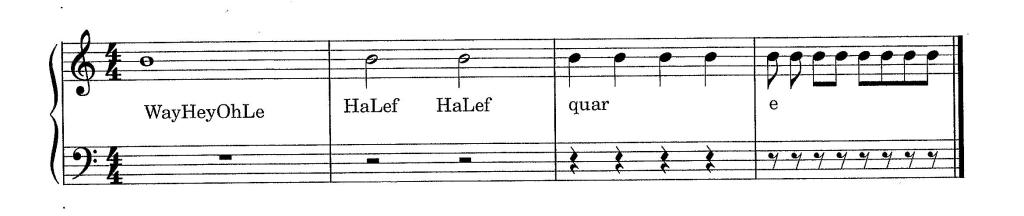

The US uses fraction names for the symbols we use to write rhythms down e.g “quarter note”. There are other names , e.g crotchet, which are used in the UK but I prefer the fraction names as they are more straightforward and also relate directly to the time signatures. Gradually while teaching rhythms a way of singing the fraction names has evolved below. For rests the fraction names are whispered. Are there similar conventions in the US? If you know of any please drop me a line.

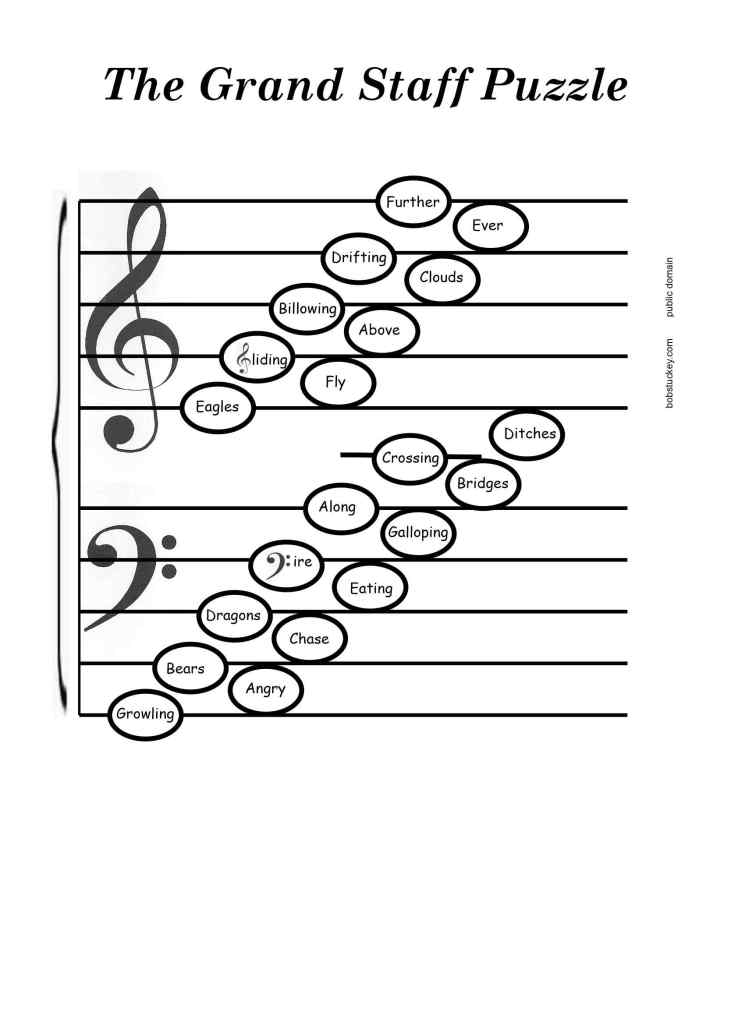

When you read this paragraph it is easy to identify each of the 26 letters by its unique shape. The piano has only 12 notes, 7 white and 5 black but when you read music notes they all look the same. Its only by counting the lines and spaces that we can find out what each note is. Most people learn how to read words but few people learn to read music, especially piano music with its treble and bass clefs which are combined into the Grand Staff. Here’s a little story to help you solve the puzzle and open the box of treasures. You may like to print it out and add some drawings about the story.

Major and minor thirds – so important to chords and scales. Sing and play this little ditty to help make them part of your experience. Major and Minor Triads and Scales.

Triads are nice to juggle. Sing this tune as you do the juggling.

The difference between major and minor thirds is the cornerstone of music theory. How can you learn to tell them apart? One way is to apply the “Frere Jacques test”. Frere Jacques uses the major third. If you try this tune on a minor third it sounds a bit miserable. Here’s the tune first in F major, then our hero protests in Dm (the relative minor sharing the same key signature) then later in F minor (the parallel minor). Did he get out of bed to ring the bells? Follow Frere Jacques’ Lament and you might find out.

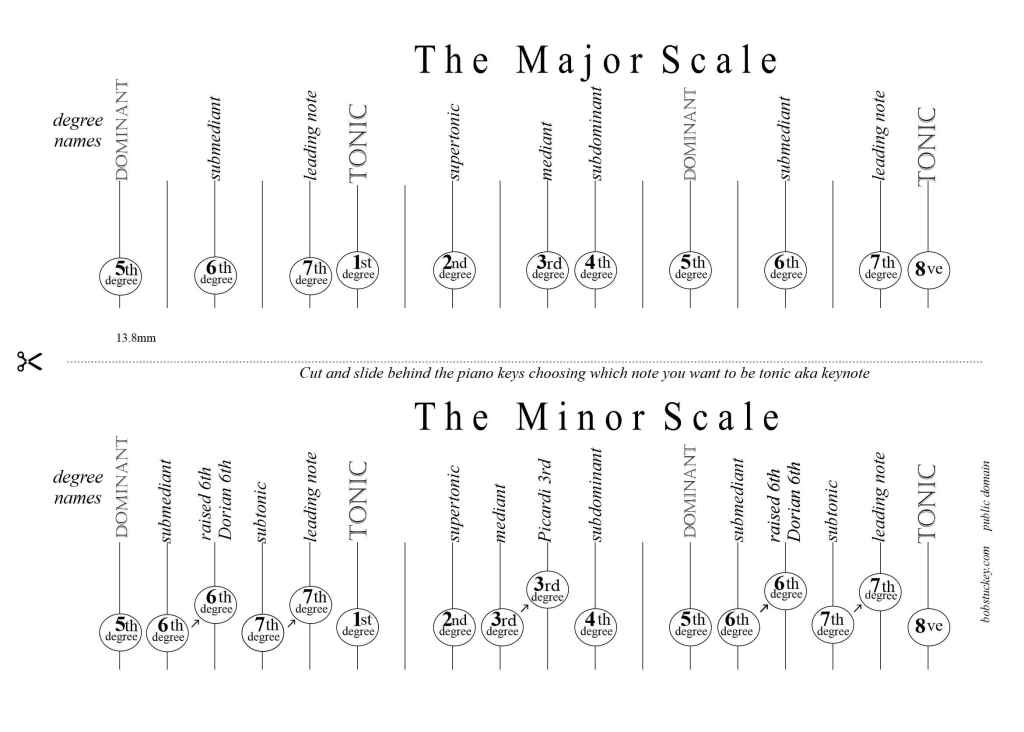

Only one major scale but all those minor scales! This song will help you hear the difference between five of them. Minors start the same… and end the same . For classical exams you can get by with the harmonic and melodic. For jazz exams you may also need the Dorian. Look for the relationship between this tune and the following chart. The 6th and 7th degrees of the minor scale, which both can be either low or high, are shown in the grey bubbles hanging below the minor keynotes.

Who was the first person to change key? How many times have we heard a key change in a song – that extra lift before the final chorus? Or we’re trying to sing a song and it seems too high or low for us. So we shift the key perhaps moving the capo on the guitar or pressing the TRANSPOSE button on the keyboard. Yet who was the first person to to realise we could move everything up or down one fret at a time? The answer is to found on the page gorzanis-1567 .

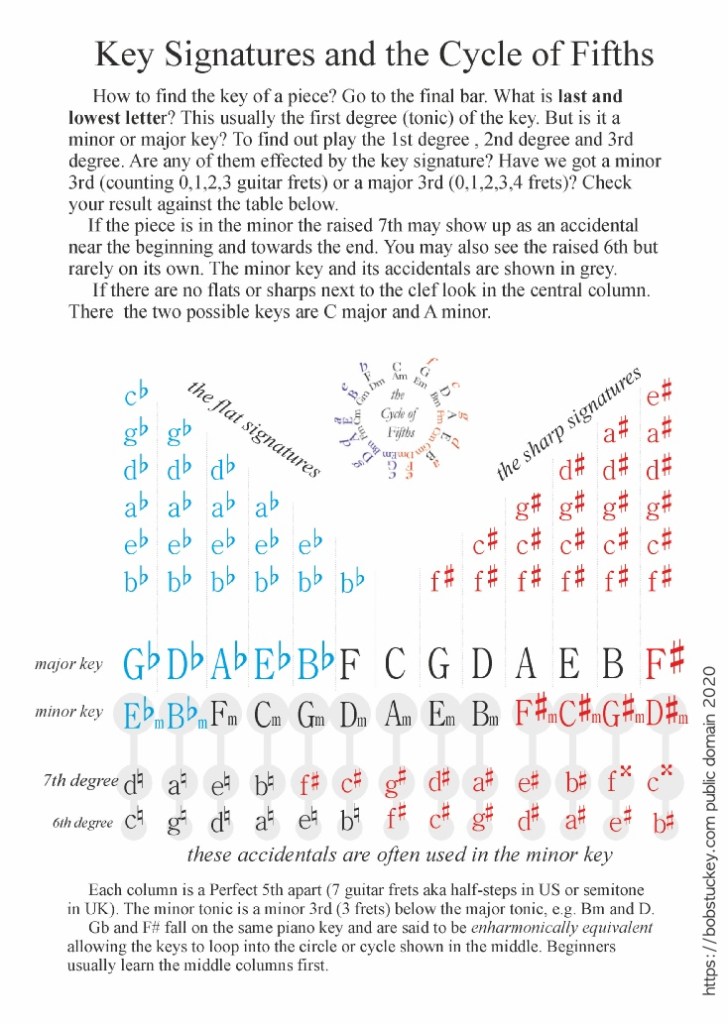

You can download a pdf version of this chart by clicking Key signatures and the Cycle of Fifths.

How can we ever remember the order of the sharps and flats in the key signature? Here’s a catchy song that you will never forget (after you have sung it three hundred times) What’s Your Sign-ature? Print it out then sing along to this track. You can also sing along reading up the list of six flats on the left and six sharps on the right that you see in the diagram above. On this track I am joined by Ruby Hamill on vocals with dad Andy on glockenspiel and audio.

Musical intervals are confusing things. You can think of them as bus stops that sometimes get moved around by the bus company when there are road works etc. They don’t want too few stops or too many stops close together. Sometimes all you need to know is the number of stops. But sometimes you just need to know the exact distance between them. For that you need a fixed unit, such as a mile. Sometimes you need to know the number of stops and the exact distance. The bus stops are your elastic 7 notes, counted 1st , 2nd, 3rd and the distance is measured in guitar frets (aka half steps or semitones) counted from 0. Put them together e.g. a 7th with 10 frets is a minor 7th.

Another way to discover the character of musical intervals is to find them on the piano keyboard. Print out the diagrms below and slot them behind the piano keys to find the major and minor scales in any key. Try the major scale first which is a little bit simpler.

The 4ths and 5thS that are used by the modern orchestra are not actually Perfect but slightly out of tune. That’s the price you pay for being able to play a melody starting on any note, black or white. If you’re interested in splitting hairs then read about equal temperament a few paragraphs lower.

It’s interesting to make various scales on one string. Imagine the open string 0 to be the bus station and fret 12 to be your destination, the same note an octave higher. Now play the frets 0 2 4 5 7 9 11 12. Looking at where the the seven bus stops were placed 1st stop fret 0, 2nd stop fret2, 3rd stop fret 4, 4th stop fret 5, 5th stop fret 7, 6th stop fret 9, 7th stop fret 11, 8th stop (the 8ve) fret 12. This is of course the major scale getting its name from the 3rd with 4 frets , the major third. Using the diagram above find the full names for the other intervals that make up the major scale.

At one time you just needed C, Cm and G7. But chord symbols have gradually grown more elaborate. Reading Chord Symbols is a guide through the rules that musicians use.to read or download. We have to know how to count round the first octave and into the second octave up to the 13th which is illustrated in this spiral.

Chord symbols started to develop around 1830 modelled on the chord buttons of the newly invented piano accordion. Before that composers since 1600 would indicate a chord by counting the intervals above the bass note, known as figured bass. It works well so long as you stay close to the key signature but gets very messy when you get more adventurous in your key changes which is what the new generations of composers wanted to do. Chord symbols, in contrast, are completely independent of key signatures.

A casualty in the changeover is the diminished triad – a delicate ambiguous sound which was originally shown as Bo meaning just B D F. In classical harmony books it still has that meaning. However if you write Bdim or Bo these days pop or jazz musicians will play the full diminished 7th, that is B D F Ab. So for that rare occasion when the diminished triad occurs in pop and jazz we could write Bo5 meaning “just the triad, please, leave out the 7th” , a bit like how B5 means bare 5th, “please, leave out the 3rd”. By taking the dim 7th as the default things look neater and simpler, e.g D-7 D#o E-7 C#o …

We can also give musicians a list with the understanding that if there are more than one symbol of which would normally be a root then none of them is a root. Brackets or underlining can also distinguish these note lists. The first is played lowest while the others can be juggled in any order e.g. in this typical Baroque chord sequence.

in letternames Gm (ACF#) Gm/Bb

in fixed solfa Sol- (LaDoFa#) Sol-/Sib

in movable solfa l– (trs#) l-/u or u- (rft) u-/mb (ut=do)

in Nashville 6m (724#) 6m/1 or 1m (247) 1m/b3

The convention could be useful for any other note combinations which can’t easily be portrayed in chord symbols e.g. (C Ab B), (CFBb), (CDB), (CF#) etc.

There are so many ways to arrange notes. How come these two scales, the major and minor, stand head and shoulders above the rest? I try to answer this question in a short essay The Ionian-Aeolian Duopoly.

Most popular songs have around seven notes per octave. More than that and the tunes becomes less memorable and spontaneously singable. Is this part of our biology? This essay discusses these issues Sharps and flats are quite natural.

The frets of the guitar shorten the string by around 1/18 each time. 12 frets shorten the string by exactly half producing a note an octave higher. But none of the notes on the way up are exactly in tune. This method is called Equal Temperament that is equal but impure. The piano and all of the instruments of the orchestra use the same method. This short essay How out of tune is Equal Temperament and how much do we care? demonstrates the arithmetic with the help of some cut out shapes.

Equal Temperament has a long history appearing in China two thousand years before it took hold in Europe and is now spread worldwide by radio, TV smart phones etc . Its progress is tracked in A Chronology of Equal Temperament and its Musical Exploration. Central to the history of Equal Temperament are the Lute Dances on Every Fret written by Gorzanis in 1567 which demonstrate that with equal frets whole pieces can be transposed. Each fret on a lute can be slid to be sharper or flatter. By experimentation lutenists found that by reducing the length of the remaining string by 1/18 twelve such frets would reach an octave and on the way get very close to all the intervals needed to make resonant major and minor chords. This is known by instrument makers as the rule of 18. I am pleased to say these lute dances have now been recorded by Michele Carreca and we have worked together to provide extensive commentary on the CD, see the gorzanis-1567 page. To celebrate the release of this CD and to celebrate the rule of 18 here is a poem Ugly Little Fretet.

Jazz musicians take the chords from a tune and say,” Lets do this as a bossa.. or a waltz or a swing?” This was also happening back in 1550 with the rhythms that were in fashion, e.g “Let’s do this as a Salterello”. I asked Miyuki Tanaka to help me make a YouTube video to demonstrate using the jazz app iReal Pro with two popular dances of the time.

A Renaissance jam session.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u7af3OQgnrs&t=5s

These are the chord sequences that lutenist Gorzanis improvised on in every key, the first person to do so in Europe back in 1567. Here’s the CD of his explorations.

https://www.ayros.eu/shop/gorzanis-1567

My dad was fond of peppering his speech with the odd Latin phrase. One that stuck with me is sine qua non – without which not – in other words something essential. The sine qua non of the luxurious harmonies we enjoy is the tuning system that originated around 1550 on the lute in the north of Italy. So for all the tuning nerds out there, its all explored in the calm presentation of a specialist on the topic, Chris Egerton https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0RAVr0TB4VM&t=49s

But all is not well in the world of harmony, with much subterfuge and rancour going on below the surface. To hear the story from all sides consult The Disharmony of Harmony.

So we have got an octave devided into 12 guitar frets. We can get to 12 in various ways:

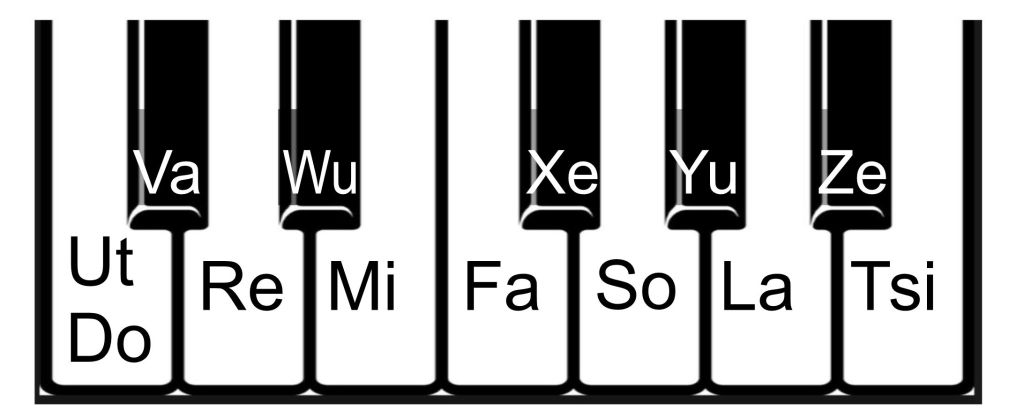

6 frets x 2, 2 frets x 6, 4 frets x 3, 3rets x 4 Each of these create special harmonic characteristics often evoking the supernatural or ghostly, perhaps becuse it is not natural for notes to stay at exactly the same interval as they get higher so these paterns can be called the Symmetricals. For this discussion we will use fixed chromatic solfege Ut=Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Tsi and Va Wu – Xe Yu Ze for the black notes

6 frets x 2 aka the tritone. e.g Mi Ze Low down the two notes sound threatening as if in competition with each other, sharing no harmonics until the around the 7th, hence the nickname “the devils interval”. But in a high range the tritone will calmly blend in as h5 and 7h of Ut or h7 and 10 of Xe. Jazz musicians often exploit this ambiguity by substuting a dominant chord e.g Sol7 with its tritone Va7, known as “tritone substitution” It may take the listener a fraction of a second to reinturpret the roles of the tritone. The ambiguity was also exploited dramatically by Rimsky-Korsakov in the trombone and trumpet fanfares a tritone apart while the strings evoke the shared h5 and h7. This can be heared at 13m 35s into this recording:

2 frets x 6 aka the wholetone scale. The notes are close together making a scale but, unusually, with the same inerval between each, Ut Re Mi Xe Yu Ze Ut, nonr of which have a perfect 5th , the usual bodyguard of a tonic. These features make it feel otherworldly

4 frets x 3 aka the augmented triad as 8 ftrets make an augmented 5th. A triad such as Ut Mi Yu could have any of the notes as root, usally the lowest one which would pair up with one of the higher notes in a h4 and h5 relationship. But three other notes may claim to be roots , Re, Xe and Ze subjugating two of the triad notes to act as h7 and h9.

3 frets x 4 aka the diminished 7th chord e.g Tsi Re Fa Yu. This would usually called B dim 7 , the lowest note assuming root status, but without any semblance of a supporting harmonic in the higher notes. In fact three of the notes would rather offer thier support to other notes, not included in the chord itself, e.g Sol for which Tsi Re and Fa can serve as h5, h6 and h7. Or they can offer similar support to other root candidates Mi , Va or Ze. In the days of silent movies the accompanying pianists often struck the dininished 7th chord to signify danger.

In contrast are the Asymmetricals, the pentanonic scale and heptatonic scale , with neither 5 nor 7 being factors of 12, e.g Ut Re Mi Sol La and Ut Re Mi Fa Sol La Tsi. Their asymmetry helps their memorability.

And a different kind of symmetry is found in “the chord of nature” the harmonic series where the first interval is an octave, then a fifth, then a fourth, each smaller than the one before, by smaller amounts.